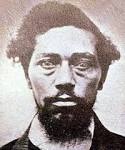

Dangerfield Newby

I know, I know it's the holiday, the endless endless holiday, but I can't get my mind off John Brown and Dangerfield Newby. This is partly due to the fact that I find myself in northern Virginia, not far from Harper's Ferry, in a town where the majority of streets appear to be named for Confederate generals and other dead slaveowners (y'know, Founding Fathers), and not far from a spot called Dangerfield Island, which is no longer an island and did not likely have anything to do with Dangerfield Newby, who, being a freed slave and the first of John Brown's followers to be killed during the raid on Harper's Ferry, was not the sort who gets things named for him in this country. I also happened to go see Lincoln the other day (blame Christmas) and have been working hard to cough that foul hairball of imperial mythmaking from my gullet. The myth in question being the usual Spielbergian vision of American history as the glorious moral arc of whiteness on the path to redemption. Be patient, dammit, we're gettin' there! John Brown had a different notion. So, I imagine, did Dangerfield Newby. For Brown, the fact of human bondage was not an unfortunate parentheses to the otherwise glorious tale of American democracy, it was a "barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion." It gave the lie to the whole affair. Amending the Constitution—which built the foundations of American governance on and around the institution of slavery without ever using the word—would not do the trick. So Brown wrote a new one and led an armed insurrection to put it in place. (His version had its problems, forbidding "filthy conversation ... intoxication" and the "unlawful intercouse of the sexes"—o beloved revolutionary saints, wherefore art thou always so fucking puritanical?) Dangerfield Newby had a much more immediate goal in mind. He was the eldest child of Henry and Elsey Newby, the former a white man, the latter his slave. In 1858, when Newby was about my age (ahem, nearing 40), his father granted him his freedom, but Newby's wife Harriet and their seven children remained enslaved to another Virginian whose farm was not far from Harper's Ferry. In just a year, Newby managed to raise more than $700 towards the asking price of $1000 for the freedom of his wife and one of their children. It was not, he knew, sufficient. "Oh Dear Dangerfield," Harriet Newby wrote in April of 1859, "com this fall with out fail monny or no money I want to see you so much that is one bright hope I have before me." Eleven days later she beseeched him again, "Com as soon as you can for nothing would give more pleasure than to see you it is the grates Comfort I have is thinking of the promist time when you will be here oh that bless hour when I shall see you once more my baby commenced to Crall to day it is very dellicate." By August she was growing desperate: "it is said Master is in want of monney so I know not what time he may sell me an then all my bright hops of the futer are blasted for there has ben one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles that is to be with you for if I thought I shoul never see you this earth would have no charms for me." Shortly thereafter, despairing of other options, Dangerfield Newby joined John Brown's band on a farm just outside of Sharpsburg, Maryland. On October 17, 1859, rifles primed, they rode south for Harper's Ferry. Late that rainy morning, while running for shelter, Newby was shot in the neck and killed. When the fighting was over, the citizens of Harper's Ferry mutilated his corpse and left his remains in a gutter for hogs to eat. Harriet's letters were found in his pockets. She and their children were later sold to a Louisiana planter. I don't want to end the story here, so I will just add, unhappily, that the story does not end here.

b.

b.

Reader Comments