Regarding the Sieve Maker of Tārāb

So I’ve been reading about the Mongols. Not for any particular reason. Mainly in a searching-for-perspective sort of way. The last thing I want is to suggest any direct analogy between the heirs of the mighty Ghengis Khan and the Rise of Trump and other petty ethno-nationalist forces across the globe. Whatever their shortcomings, the Mongols were a proud lot, possessed with an overabundance of vigor. By contrast, however febrile and giddy Trump and Co. may be at the moment, they are a frightened, resentful, and backwards-looking bunch. Even in victory, their voices shake.

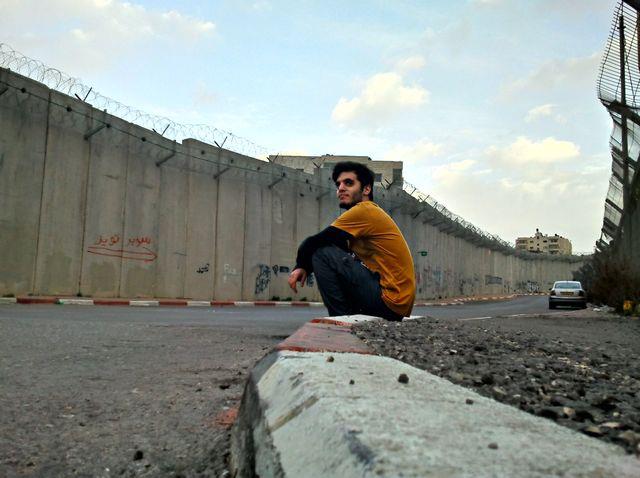

By that perhaps over-broad “Co.,” I mean the authoritarian ethno-religious chauvinism in vogue from Istanbul to East Anglia, Budapest to Jerusalem to Warsaw to Calais. And Manila and Moscow and New Delhi. Etc.

The Mongols made the earth shake. Their conquests, in a very few years, spread from the Central Asian steppe north to Siberia, south into India, west to Central Europe, and east to the Sea of Japan. They would quickly establish what remains the largest land empire in the history of humankind. One little side note: In January of 1260, two years after laying waste to Baghdad, then a city of unrivaled beauty, scholarship and artistry, the armies of Genghis Khan’s grandson Hulagu laid siege to Aleppo. Aided by Frankish and Armenian Christian forces eager to push the Muslim Ayyubids from the Levant, they leveled the already-ancient city, burned its great mosque, and enslaved those few of its inhabitants whom they did not slaughter. The mosque would be rebuilt by the Mamluks and would stand for another 700 years, until April of 2013.

I’m getting ahead of myself. In 1220, Ghengis Khan’s armies, “more numerous than ants or locusts,” arrived outside the gates of Bukhara, in what is now Uzbekistan and what was then one of the great centers of medieval Muslim learning. The city surrendered and the great Khan gathered its notables into the mosque and addressed them: “O people, know that you have committed great sins, and that the great ones among you have committed these sins. If you ask me what proof I have for these words, I say it is because I am the punishment of God. If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.”

That, my friends, is a victory speech. Genghis Khan did not hunch over his iPhone at four a.m., oozing tweets like pus from an abscess.

In any case, he proceeded to burn the city. “And the people of Bukhara, because of the desolation, were scattered like the constellation of the Bear and departed into the villages, while the site of the town ‘became like a level plain.’”

But the point of all this comes on the next page of the Persian historian Atâ-Malek Juvaini’s History of a World Conqueror. Eight years after the sacking of Bukhara, writes Juvaini, “a sieve maker of Tārāb in the district of Bukhara rose up in rebellion in the dress of the people of rags, and the common people rallied to his standard.” Juvaini, who had ingratiated himself in the Mongol court, describes the rebel leader with undisguised contempt. Still, we learn from him that the poor came to Mahmud the sieve maker of Tārāb as they once did to Jesus of Galilee: to heal the sick and the paralyzed, to restore sight to the blind. He was said to converse with jinns, or spirits, who, “informed him of what was hidden.” When Mahmud the sieve maker of Tārāb entered the city of Bukhara, the alleys of the market were so crowded with people eager for his blessing that “there was not even room for a cat to pass.” He had in mind a more holistic sort of healing, and instructed the poor to arm themselves with whatever weapons they could find. “My army is partly visible, consisting of men,” he announced, “and partly invisible, consisting of the heavenly hosts, which fly in the air, and of the tribe of the jinns, which walk on the earth.” And so the poor of Bukhara soon took the town and plundered the houses of the wealthy.

Running for their lives, the city’s emirs and notables sought the assistance of the Mongols. They gathered an army, and marched to retake Bukhara. Surrounded by many thousands of his followers among “the people of rags,” Mahmud the sieve maker stood to meet the occupier’s armies without a weapon in his hand nd without armor to protect his body. “At this juncture a strong wind arose and the dust was stirred up to such an extent that they could not see one another.” Believing the storm a miracle, the Mongols and the armies of the wealthy fled. The people in the villages rose against them with spades and axes, slaughtering them as they ran: “… especially if he was a tax-gatherer or a landowner, they seized him and battered in his head.” Nearly ten thousand were slain in this way, Juvaini writes. But Mahmud was killed by an arrow and when the Mongol armies returned and his followers took to the field without him, again without armor, twenty thousand rebels met their deaths. The uprising was defeated.

And so, as we greet the new year, let us not fear, but remember that all mighty empires fall and that no matter who records the history, brave men and women invariably stand against them. And let us remember that even unarmed and outnumbered, we are protected by invisible armies and by the great and immortal tribe of the jinns, and that we sometimes, briefly, win.

b.

b.